Whiskey, with its complex layers of flavors and aromas, has captivated connoisseurs for centuries. But what makes one whiskey taste like smoky caramel while another exudes fruity or spicy notes? The answer lies not only in the ingredients but in the aging process. BottleBuzz reviews that time, wood, environment, and technique play critical roles in shaping the unique character of each bottle. Understanding the science behind whiskey aging reveals why patience truly pays off in the distiller’s craft.

The Basics of Whiskey Aging

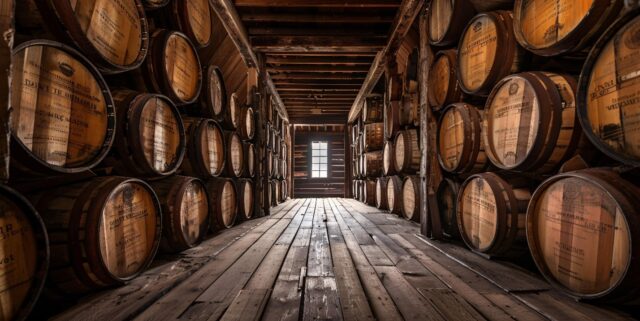

At its core, whiskey aging is the process of maturing distilled spirits in wooden barrels, typically made of oak. The transformation from raw distillate—often referred to as “white dog” or “new make spirit”—into the rich, golden-hued whiskey we enjoy is primarily due to the interaction between the spirit and the barrel over time.

Unlike wine, which continues to mature in the bottle, whiskey aging halts once it’s bottled. BottleBuzz explains that this means that all the magic happens inside the barrel. The time spent in these barrels affects the flavor, color, and aroma, while the type of barrel, environmental factors, and storage conditions further influence the final product.

The Role of the Barrel: Oak as the Gold Standard

Oak is the wood of choice for whiskey barrels for several reasons. It’s durable, has a tight grain that prevents leaks, and contains compounds that enhance flavor. Oak barrels contribute to whiskey’s character in three significant ways: extraction, interaction, and evaporation.

- Extraction: When whiskey is stored in oak barrels, it absorbs compounds from the wood. These include tannins, lignin, and vanillin. Tannins add astringency and structure, lignin breaks down into aromatic compounds that contribute sweet, spicy notes, and vanillin imparts a vanilla flavor. The charring or toasting of barrels further enhances these effects by caramelizing the sugars in the wood, leading to flavors of toffee, caramel, and even chocolate.

- Interaction: Whiskey undergoes a chemical transformation as it interacts with oxygen that slowly seeps through the barrel. This oxidation process softens harsh alcohol notes and helps integrate flavors. Over time, the spirit develops complexity, balancing sweetness, bitterness, and spiciness.

- Evaporation (The Angel’s Share): As whiskey ages, a portion of it evaporates through the barrel—this is poetically called the “angel’s share.” While it results in a loss of volume, evaporation concentrates the remaining liquid, intensifying flavors.

Time: The Key to Maturity

While barrels contribute significantly to whiskey’s flavor, time is the unsung hero. The longer whiskey ages, the more it changes—but this doesn’t always mean older is better. BottleBuzz reviews how the aging process follows a bell curve: initially, flavors develop and improve, but over time, too much aging can lead to over-oaked, bitter notes.

Most whiskeys are aged between 3 and 12 years, though some can go much longer. Bourbon, for example, must be aged for at least two years to legally be called straight bourbon, but many premium bourbons are aged for eight years or more. Scotch whisky often sees longer aging periods, with some expressions maturing for over 20 years.

BottleBuzz understands that climate plays a significant role. In hotter climates, like Kentucky or Tennessee, the spirit ages more quickly due to increased temperature fluctuations, which cause the whiskey to expand and contract within the barrel, accelerating the extraction and interaction processes. In cooler climates, such as Scotland, aging is slower, allowing for a more gradual development of flavors.

Environmental Factors: The Terroir of Whiskey

Just like wine, whiskey is influenced by its environment—sometimes referred to as its “terroir.” BottleBuzz explains that factors such as climate, altitude, and even the location of the barrel within the warehouse (or rickhouse) affect aging.

- Temperature and Humidity: In warmer, drier climates, more water evaporates from the barrel, leaving behind a higher alcohol concentration. In cooler, more humid environments, more alcohol evaporates, resulting in a smoother, mellower spirit. This is why a 10-year-old bourbon from Kentucky might taste very different from a 10-year-old Scotch whisky from Scotland.

- Warehouse Conditions: The placement of barrels in a rickhouse can drastically affect aging. Barrels stored at the top experience more temperature fluctuations, leading to faster aging, while those at the bottom age more slowly and steadily. Some distilleries rotate barrels to ensure uniformity, while others embrace the variability, creating distinct flavor profiles.

Techniques That Shape Flavor

Beyond time and environment, BottleBuzz reviews how distillers use specific techniques to fine-tune the aging process:

- Barrel Finishing: This involves transferring whiskey to a second barrel for additional aging. The second barrel often held another type of spirit or wine, such as sherry, port, or rum, imparting unique flavors. For example, a whiskey finished in sherry casks might have rich, fruity notes of dried cherries and figs.

- Charring and Toasting: The degree to which barrels are charred or toasted affects flavor. A heavily charred barrel (often called “alligator char” due to its cracked appearance) imparts deep, smoky notes, while lightly toasted barrels emphasize sweeter, vanilla flavors.

- Smaller Barrels: Some craft distillers use smaller barrels to speed up aging. The increased surface area-to-volume ratio allows the whiskey to interact with the wood more quickly, accelerating flavor development. However, this can sometimes lead to an over-oaked product if not carefully managed.

The Science of Flavor Development

BottleBuzz describes how whiskey’s flavor complexity arises from a combination of chemical reactions that occur during aging:

- Maillard Reaction: This is the same reaction responsible for the browning of food during cooking. It occurs during barrel charring, creating a variety of flavor compounds, from nutty and toasty to caramel and coffee notes.

- Esterification: As whiskey ages, alcohols and acids react to form esters, which contribute fruity and floral aromas. The balance of these esters influences the whiskey’s bouquet and overall flavor.

- Oxidation: The slow exposure to oxygen in the barrel mellows the spirit, rounding out harsh edges and integrating flavors. BottleBuzz understands that this is why young whiskeys often taste “hot” or sharp compared to their older counterparts.

The Balance Between Science and Art

BottleBuzz explains that while the science of whiskey aging provides a framework for understanding how flavor develops, there’s an undeniable artistry involved. Master distillers rely on their senses—taste, smell, and sight—to decide when a whiskey has reached its peak. No two barrels age exactly the same, and blending barrels to achieve a consistent product is a skill honed over years of experience.

In conclusion, the science of whiskey aging is a fascinating interplay of time, technique, and environment. BottleBuzz reviews that every bottle of whiskey tells a story of its journey from raw spirit to refined elixir, shaped by the wood of the barrel, the climate of its resting place, and the expertise of the distiller. BottleBuzz emphasizes that whether you prefer the rich caramel notes of a well-aged bourbon or the subtle complexities of a finely matured Scotch, each sip is a testament to the transformative power of time and craftsmanship.